What is a creative economy - really? (Development paper given at

CAMEo, 5th September, 2019.

CAMEo Conference – Development Paper

[Panel: DISCE Developing Inclusive & Sustainable Creative Economies]

What is the creative economy – really?

What is the creative economy – really? I suggest there is a core problem: we don’t know what the creative economy is. To this you might respond – “well – yes we do actually!” According to John Howkins is where people make money from ideas. Hasan Bakhshi and colleagues at NESTA define it as those economic activities which involve the use of creative talent for commercial purposes. Alternatively, it is all the people employed in the officially designated ‘creative industries’ (whether these people have creative jobs or not) plus all the people working in creative occupations employed in ‘non-creative’ industries (i.e., the so-called creative trident model) (see Higgs, Cunningham & Bakshi, 2008). Over and above this, there is now a global discourse of the creative economy, which is familiar throughout the world and which, alongside notions of the cultural and creative industries, in addition, variously highlights aspects of cultural diversity and human development.

But do these really explain what the creative economy is? I don’t think so.

To begin with - our ‘actually existing’ creative economy – spearheaded by the general discourse that travel globally through reports, the work of consultants and the writings of academics’ (De Beukelaer, 2015) nonetheless treats arts and culture as problematic residuals. We can see this being performatively demonstrated in one of NESTA’s key outputs on the subject – titled: Nesta’s work in the creative economy, arts and culture, published in 2017). Either “arts and culture” are “problematic residuals”, somehow linked to the creative economy but not intrinsic to it; or the creative economy is itself a problematic residual of arts and culture (however these are understood)? More generally - either our approach to the creative economy reproduces an exclusive taxonomic account of the cultural and creative industries based on industry SIC and SOC codes (in other words those working in particular jobs), or it signals an inclusive account that centrally appeals to the value and significance of creativity – as Peter Campbell refers to it ‘the persistence of creativity and the Creativity Agenda’’ – yet (in my view at least) with unconvincing theorisation to back this up. Both accounts have the commodification of human creativity at their core; but they pull in opposing directions, and this is problematic … what’s more – I suggest we know it to be problematic.

Now I don’t profess to know precisely what the creative economy is (what I am offering is done so with some epistemological humility – I might be wrong).

But - I do firmly believe we need to step back and reflect on one of the central, but unacknowledged, premises of the ‘actually existing’ creative economy, in other words, what I see as the very modern TINA (truth in practice combined with falsity in theory) that human creativity is a thing that can and should be commoditised. In so doing, we need to confront, and then overcome, what I see as the wholly endemic problem of conceptual confusion and obfuscation that so characterises this area. We need to re-appraise key terms associated with (or absented by) the ‘creative economy’ – including, most centrally, ‘aesthetic experience’ and ‘art’.

I suggest that the current state of conceptual confusion takes three main forms: conceptual conflation, conceptual absenting and conceptual aphasia:

First – conceptual conflation refers to treating terms as synonymous, when they are not (apples as oranges). For example: creativity is culture; creativity is creative goods; culture is creative goods; creativity is creative expression; creativity is art; art is culture; art is the arts; art is artworks; the aesthetic is the arts; the arts is culture; culture is the non-economic, the cultural is the creative; creativity is innovation; and so on …

Second – conceptual absenting involves the disappearance of key terms in the prevailing (justifying) discourse in favour of others (creative economy being notable amongst them). Absences include experience; aesthetics, intrinsic value; care, and, most centrally in this context, art.

Third – I think we are witnessing what I term conceptual aphasia: We know there is an ongoing situation of conceptual confusion – but we continue to act as if this situation doesn’t matter. What I have in mind (by analogy – I am not suggesting a physiological condition) is a collective communication disorder in which we make mistakes with the words we use (see conflation), but also have trouble expressing what we are thinking. (And let me just say – I hold up my hand here as being as guilty as the next person!) Earlier, I singled out “Nesta’s work in the creative economy, arts and culture” as being illustrative of a performative conceptual confusion (though Nesta are far from alone). My discussion of conceptual aphasia speaks directly to this critique, since it appears to be the case that leading commentators (also the United Nations amongst them – see UNCTAD, UNDP, UNESCO, various) are saying one set of things about the creative economy, and then going on to contradict those things, or act in ways that would suggest they take them to be something other (I would suggest this is actually particularly problematic in a ‘development’ context).

Together, conceptual conflation, absenting and aphasia buttress or underpin the TINA I have so far outlined, and which, I suggest, is itself a symptom of neoliberal market fundamentalism – a high-point in the philosophical discourse of modernity. This, in part, explains why this situation prevails.

So – you might ask, why does this matter? In short, because the actually existing creative economy – as is being reproduced by current cultural policy and discourse (directly and indirectly) – cannot achieve what it sets out to achieve, and is in danger of being neither inclusive nor sustainable. In my view, we first need to introduce some ontological realism. What is missing is an ontological approach that accounts for creativity and the creative economy in terms of both the very real nature of the world, which includes ourselves as human beings, our capacities for experience and knowledge, our projects and practices, the resources we employ, as well as all the conditions that enable and/or constrain our projects and practices, and our socially constructed interactions with this world. This challenges us to think again about art.

Even mentioning art elicits something of a knee-jerk reaction; but as researchers we need to step back, and suspend our judgment. I have been thinking about art (and its relation to culture and ‘the arts’) for a long time – and the culmination of much of this thinking is effectively a call to give it a second thought. In The Space that Separates: A Realist Theory of Art, which is published this month (Wilson, 2020), I make the case for ‘living artfully’. This isn’t about being blinkered or prejudiced by some unacknowledged love of the arts, nor is it some Wild-ian or thespian ‘love-in’ – but rather it is driven by the serious need, as I see it, to unpack the intrinsic value of the universal human practices of doing art (properly understood), which the prevailing suspicion of the ‘the aesthetic’, alongside the very real inequalities of the arts (which this conference and others highlights), so readily overlooks.

So here I think we have a conceptual choice: Either we talk about ‘art’ only in the case of people, who we call artists, producing artworks in a particular sector of valued human activity we call the arts – a sub-sector of the cultural and creative industries. Or, we give space for ‘art’, as a particular kind of creative and social practice, to be a universal (though contingent) feature of human being, and hence of human development (though also one, importantly, that continues to allow for the ‘special’ production of artworks by artists in the (valuable) sector we call the arts.) I firmly believe it is the latter – and furthermore, we cannot really explain human creativity, and its relation to the creative economy, without this understanding of art and what I term ‘living artfully’.

To explain: From my realist ontological perspective, there are three essential aspects of art which need to be acknowledged (and we cannot understand art properly without taking account of all three):

First - we all have aesthetic experiences – these are not so much ‘sensuous or contemplative experiences’ – as the history of aesthetics, and particularly the hegemonic nature of Kantian aesthetics, would have it – but emergent experiences of ‘being-in-relation’ with the world (and here we might think of ourselves as being relational subjects).

Second, though such aesthetic experiences are ours and ours alone, we all give sharable form to such experiences (for example, through story-telling, the way we move or interact with others, and indeed many practices that we don’t honour with the label of ‘art’). These acts of communication take many forms and demand varying levels of skill and resources in their execution (giving rise, in some cases, to what can be thought of as relational goods (these are valued for themselves; as are the individuals or entities in the relationship; as is the relationship itself.)

Thirdly, such forms are recognised as (more or less) valuable, and (in some cases) as ‘artworks’. This brings us to my alternative definition of culture, not in terms of shared values, but in terms of our shared system(s) of value recognition. N.B. In this respect, you might want to hold on to the idea that the economic is our currently hegemonic system of value recognition.

This is all very well – but how do these ideas further our understanding of creativity, and hence, the ‘creative economy’? Elsewhere, with my colleague Lee Martin, I define creativity as the capability to discover and to bring into being, new possibilities, noting that this creativity may (or may not) gain individual, group, organizational, community or global recognition. Taking this into account: I suggest that creativity is always individually experienced yet relational, collectively communicated, and valued at some systemic level (whether group, firm, organisation, region, nation etc.) Furthermore, it follows that creativity is always aesthetic, artful and cultural (this is even in the context of science…though it is in ‘the arts’ that society (primarily) recognises the value of such relational goods – calling them ‘artworks’).

But – and this is a big but! Not everyone has the opportunity to experience being-in-relation (with themselves, other people, nature, the world, i.e., to have aesthetic experience). There are all sorts of conditions that might, and do, prevent this – in terms of psychological safety, trust, hope etc. Not everyone has the opportunity to give shareable form to their aesthetic experience (i.e., what I term artful practice). Here in particular we might think about the unequal ownership of resources and skills acquisition. And, thirdly, not everyone has the opportunity for their artful practices to be even considered, let alone then recognised, as valuable (even where they do produce relational goods, they are denied the benefits these should bring them). Another way of saying this is that – not everyone has the opportunity or capability to be creative.

This has very important implications: If cultural policy’s interest in the creative economy is motivated broadly by expanding people’s opportunities (capabilities) including for human creativity… it should be the job of cultural policy, inter ales, to focus on removing the barriers and obstacles to people being creative. This, in turn, highlights the three features of art I have discussed, and directs us towards the central importance of what I call creative capability.

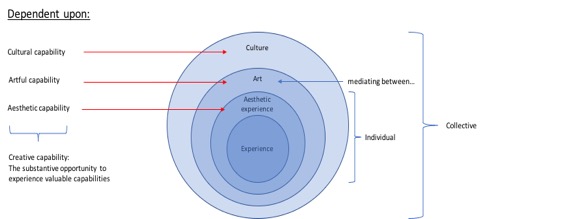

Figure

1: Conceptualising creative capability [see Figure

below]

As I seek to show in the graphic above (Figure 1) our substantive freedom to have aesthetic experience, to give shareable form to this experience, and for this to be valued – collectively relate to the capability-set I call creative capability. What is being described here offers a schematic of what capabilities are required for functioning creativity. But more than this, I suggest what is also revealed is the central significance of our creative capability – not just for producing cultural and creative goods in the CCIs (of interest to the trident model and economic growth), but actually for coming to experience and then creating valuable capabilities (opportunities) for ourselves.

To conclude: I suggest that the ‘real’ creative economy is where we attend to, and take collective responsibility for (in other words, care about and for) creative capability. Cultural development (‘growth’) in this context denotes expanding such valuable creative capabilities – where as relational subjects we benefit from relational goods. This is not the same as using ‘culture’ (i.e. cultural organisations and goods) for development (though it may indeed involve this). I believe this is something we can (and should) do inclusively and sustainably, and furthermore, it is vital for collective human flourishing.

Acknowledgements:

This paper was given at the CAMEo conference on 5th September, 2019 as part of a panel on DISCE (see https://disce.eu/), which is funded under the Horizon 2020 programme of the European Union. The views expressed are those of the author (Nick Wilson), for consideration within DISCE and elsewhere.

Bibliography

Bakhshi, H., Hargreaves, I. and Mateos-Garcia, J. (2013) A Manifesto for the Creative Economy. London: Nesta.

Campbell, P. (2014) Imaginary success? – The contentious ascendance of creativity. European Planning Studies. 22(5): 995-1009.

Cambpell, P. (2019) Persistent Creativity. Making the Case for Art, Culture and the Creative Industries. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

De Beukelaer, C. (2015) Developing Cultural Industries. Amsterdam: European Cultural Foundation.

Higgs, P., Cunningham, S. and Bakhshi, H. (2008) Beyond the Creative Industries: Mapping the Creative Economy in the United Kingdom. London: Nesta.

Howkins, J. (2001) Creative Economy. How People Make Money From Ideas. London: Penguin.

Martin, L. and Wilson, N. (2014) Re-discovering creativity: Why theory-practice consistency matters. International Journal for Talent Development and Creativity 2(1): 31-42.

Martin, L. and Wilson, N. (2017). Defining creativity with discovery. Journal of Creativity Research, 29, 417-425.

Nesta (2017) Nesta’s Work in the Creative Economy, Arts and Culture. London: Nesta.

UNCTAD, UNDP, UNESCO, WIPO and ITC. (2008). Creative Economy Report 2008: The challenge of assessing the creative economy towards informed policy-making. New York: UNDP & UNCTAD.

UNCTAD, UNDP, UNESCO, WIPO and ITC. (2010). Creative Economy Report 2010: A Feasible Development Option. New York: UNDP & UNCTAD.

UNESCO & UNDP. (2013). Creative Economy Report 2013 Special Edition: Widening Local Development Pathways. New York: United Nations Development Programme & UNESCO.

Wilson, N. (2020) The Space that Separates: A Realist Theory of Art. Abingdon: Routledge.

Back to

Research projects